Silvie has hosted apprentices interested in becoming a professional potter or studio artist in her studio for 26 years.

Past Apprentices

Current apprentice Kayla Corradi2021-

“I believe there is a sublime beauty in wild clay that deserves to be uncovered and exposed. Clay is something we walk on daily without noticing and through this practice I aim to fill the gap between humans and the nature that surrounds them.”

Kayla Corradi is a ceramic artist from New Jersey. After graduating from Messiah University in 2022 with her BFA and concentration in 3 dimensions, Kayla has continued her work with wild clay and plans on furthering this practice in the future.

Click here to visit Kayla’s website!

Kayla Corradi is a ceramic artist from New Jersey. After graduating from Messiah University in 2022 with her BFA and concentration in 3 dimensions, Kayla has continued her work with wild clay and plans on furthering this practice in the future.

Click here to visit Kayla’s website!

Elizabeth McAdams2019-2021

Elizabeth is a North Carolina native who grew up on her family’s farm in Efland, NC. She graduated from the University of North Carolina at Wilmington with a degree in studio art and minor in art history. She has most recently worked as a studio assistant for Sugar Maples Center for Creative Arts, was the working artist for Longwood University in Farmville, Va, and did a year-long wood firing ceramics residency at Cub Creek Foundation in Appomattox, VA.

Visit Elizabeth’s site

Visit Elizabeth’s site

Greta WilstermanApprentice 2017-2019

Greta is a potter from New England. She received her B.F.A from the Maine College of Art with a major in Ceramics and a minor in Art History. The convergence of a long time interest in the value of domesticity, cooking, and craft process began a love for exploring the subtleties of clay as a functional medium.

Visit Greta’s website

Visit Greta’s website

Lucas JankovskyApprentice 2015-2017

Lucas is a sculptural artist from northwest Georgia. He received his B.F.A in 2013 from Kennesaw State University. Lucas has worked for several professional artists in a wide range of processes. Including clay modeling, stainless steel/ bronze fabrication, public art installation, woodworking, and mold-making for public bronzes.

Abby ReczekApprentice 2013-2015

“I like to think of my pottery as a bond to the earth in its purest form. It continues to mimic the earth even after it has been extracted and manipulated. Respect for the earth is something that I strive to embrace throughout the entire process of making pots and which I honor through the designs that are carved into the forms.”

Visit Abby’s website

Visit Abby’s website

Andrea DennistonApprentice 2011-2013

“Through my pots I aspire to add pomp to daily living. I combine the necessary with the unnecessary – utility and ornament. In doing so, I work to make unique and engaging objects. My hope is that the pots I create spur curiosity in others by requiring them to look closely with both their hands and their eyes, as a visual examination alone is not enough.”

Visit Andrea’s website

Visit Andrea’s website

Seth GuzovskyApprentice, 2013

“Throwing uniform vessels with voluptuous curves and clean lines comforts me. Fun for me is filling tables and shelves with consistent curves and functional forms. Altering these vessels immediately after the wheel stops, allows me to stretch the bellies and reshape the lips of my pots.”

Visit Seth’s website

Visit Seth’s website

Jessica WertzApprentice, 2010-2013

“My family’s tradition of eating meals together has taught me the importance that pots facilitate in bringing people together. Pots offer a unique tactile relationship and I elevate them to the ideal that a culture is rich when it can (visually and emotionally) coalesce engaging art with an everyday purpose and function.”

Visit Jessica’s website

Visit Jessica’s website

Wendy Wrenn WerstleinApprentice 2009-2011

“My work is moving towards a more organic appearance, often altered away from the perfect circle of the wheel. Through these forms and patterns emerge lines of communication. I am learning that the communication of pottery happens most often in the absence of language.”

Visit Wendy’s website

Visit Wendy’s website

Sarah Camille WilsonApprentice 2008-2010

“The materiality of clay is indispensable to the construction of my work. Through ruptures in the surface of the clay, I convey the interiority of the object, and suggest things beneath the surface that are neither visible nor understood.”

Visit Sarah’s website

Visit Sarah’s website

Dandee PatteeApprentice 2007-2008

Dandee makes functional pieces that display abundance and benevolence. Functional pottery has a rich history. She plays with that history and makes her pieces appear as if they are overflowing with plenty.

Dandee’s Facebook page

Dandee’s Facebook page

Elisa Di FeoApprentice 2005-2007

“The acts of conveying sustenance and of personal intimacy are characteristics of functional pottery that interest me, and I convey those ideas into my current work to heighten a sense of intimacy and accessibility.”

Visit Elisa’s website

Visit Elisa’s website

Brian JonesApprentice 2003-2005

Brian shows work nationally and has been a resident artist at Watershed Center for Ceramic Arts and The Clay Studio in Philadelphia, PA. Jones lives in Portland.

Visit Brian’s website

Visit Brian’s website

Anna MetcalfeApprentice 2001-2003

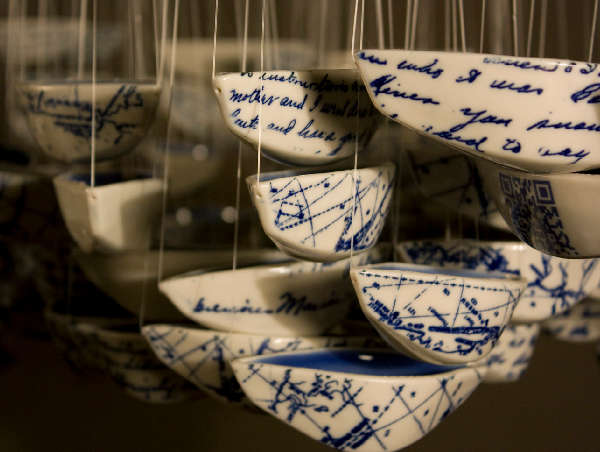

Interested in the junction of public art and craft, she makes work inspired by water, agriculture, food and community. As a teaching artist, Metcalfe loves to promote collaboration and interdisciplinary learning environments between the sciences and art-making.

Visit Anna’s website

Visit Anna’s website

Ian AndersonApprentice 1999-2001

Ian has exhibited work nationally, and received the Mentor Program Award from the American Craft Council in 2005. He has taught Ceramics at Rowan University, The Clay Studio, The Ceramic Shop, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and Penland School of Arts and Crafts.

Jerilyn VirdenApprentice, 1997-1999

Using the vernacular of the vessel, I use earthenware clay to create intimate spaces. Each form employs a language that reveals its intentions. My interest lies in the slight shifts within the arc of a bowl that determines the nature of the containment. Looking to primitive objects that have a contemporary relevance, I pare down forms and exaggerate isolated elements accentuating their sense of generosity and strength.

Visit Jerilyn’s website

Visit Jerilyn’s website