Published Articles

Below you’ll find articles I’ve written for Ceramic Monthly and Studio Potter magazines describing my studio practice. A third excerpt from the book, Handbuilt Tableware by Kathy Triplett, describing the surface decoration I use on some of my pottery. Click on the titles below to read an article.

The Potter’s Life: Deeply Invested

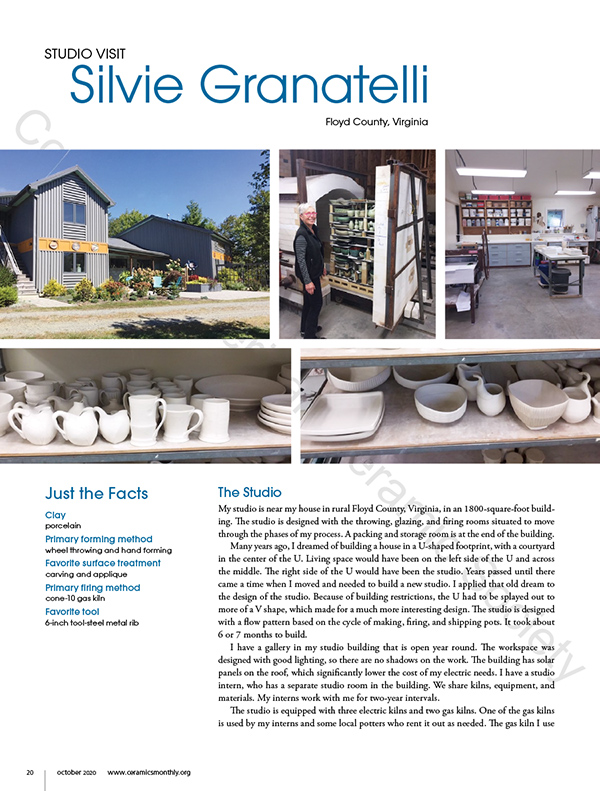

from The Potter’s Life: Deeply Invested, Ceramics Monthly, June/July/August, 2008

Silvie Granatelli in the studio

The first time I touched clay was at the Kansas City Art Institute in 1966. From that moment on, my life revolved around figuring out how to make a living with ceramics. In the ‘60s there were not many contemporary examples of studio potters, but Ken Ferguson, my professor, made his students aware that being a professional potter was a real possibility. At that time, the many things I didn’t know were a blessing. I thought everything was possible. After graduate school I worked in several communal studios in and around my native Chicago. Then, in pursuit of a fully unified combination of life and work, I made my way South.

As a young potter, my central goal was to make a seamless balance between my studio work and my domestic life. I wanted very much to live next door to the studio and make my living through my hands. After many fits and starts, I ended up in Floyd, Virginia, where I set up a studio. To earn my income, I spent the first twenty years of my career doing craft shows and selling wholesale to galleries. I also did workshops, which greatly supplemented my income.

It was initially difficult to figure out the perfect balance between the options. The upside of craft shows was the direct interaction between my audience and myself. Because of this intimacy, craft shows were a great place to see how people reacted to new work. I had to sit next to my pots and look at them in a 10’ by 10’ booth for sometimes as long as five days. It wasn’t hard to figure out what was working and what wasn’t. Selling pots at a craft show is like handing everyone your heart on a plate with a knife and fork. It can be a very vulnerable experience.

The real downside of doing craft shows was the amount of time I had to spend away from the studio. In that regard, selling pots wholesale was a boon, allowing me to stay home and work. But the equation worked only if I could manage to spend the right amount of time filling orders while still sustaining a large enough percent of my income. Filling wholesale orders had its drawbacks, too – I realized I just had to make too many pots!

Of all my income options, traveling to teach workshops was perhaps the most gratifying and fulfilling. While standing in front of students, I was able to further articulate my ideas, work on new forms as demonstration pieces and visit wonderful places. The experience also put me in touch with other artists with dynamic intellects and powerful vision, whose company I greatly valued.

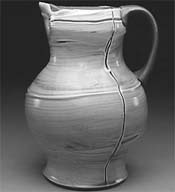

Swan handle pitchers, 5″ tall.

Over the past ten years, I have developed a new and more stable source of income by working closely with a group of craftsmen who live in my community. Together, we started 16 Hands, an art collective whose main approach to selling work is a self-guided tour of our studios. Through this tour, held twice a year, and through year-round sales in my studio gallery, I am able to generate most of my income. To make up the remainder, I still do workshops and participate in shows at galleries around the country.

In hindsight, I realize it was fortuitous that I settled in a location where the cost of living was affordable. I own a home and property near a small river in southwest Virginia, and I have health insurance and a retirement account. Health insurance is expensive for the self-employed. In fact, it is my largest yearly bill.

I am also frugal and conscientious of my spending habits. I don’t take out loans to pay for more equipment, additions to the studio, or advertising. Instead, I take on small teaching jobs, workshops, or make special order pottery. I also save 20% to 30% of my yearly income, which has provided a cushion to work from. I consider this money fluidly available for use throughout the year. And if it is not used, at the end of the year I invest it in something I need. I do my own bookkeeping but hire an accountant for taxes, a habit I’ve kept from even my poorest days. This financial plan has held me in good stead for years, allowing me to travel and cook gourmet food, two of my favorite pastimes.

I’ve been fortunate to undergo my professional maturation surrounded by a group of potters in Floyd, VA and the surrounding area. Happenstance has brought us together, connected by like-mindedness and mutual respect. When I moved to Floyd and began my career as a studio potter, I never knew how important these relationships would turn out to be. Now, after years of helping each other with technical problems, sharing trips to craft shows, and giving each other advise on both business and personal life issues, I can’t imagine a life without our close-knit community of artists.

If I have a business philosophy, it begins with the fact that I chose this life for a reason and I am willing to invest in it deeply. I take my work and my life seriously, and I believe this attention has given me a useful perspective and solid foundation. I’ve also learned that investing in myself helps other people take me seriously as well. As a potter, all you have is your pots, the way you present them, and yourself. If you want to succeed, you have to seriously consider what it takes to get the presentation right. I have a web site, business cards and well-designed brochures advertising the 16 Hands tour. These advertising tools help make my work visible to the public. And, perhaps most importantly, I never say no to an opportunity that might help me grow in my field. In fact, there have been many times when I was in way over my head, (especially when giving presentations that were not demonstration oriented), but I never walked away from any of them wishing I hadn’t participated.

Over the past 10 years, I have developed an assistantship program. Through this program, I give young potters a chance to witness my own process, as well as my business acumen, and to test out a potter’s life before they make their own full investment. They work with me for two years and during that time, they learn what it takes to develop an artists intuition, to refine the rhythm of a potter’s life, to develop a body of marketable work, and, finally, to start selling their work professionally.

Breakfast/lunch sets, slip cast porcelain

As much as I love pots and collect them, I don’t actually derive most of my inspiration from pottery. I travel a great deal, spending time in the outdoors and, perhaps paradoxically, the inside of museums (which, of course, house so many representations of nature.) In all of these places I draw “things.” It could be the form of a flower that reminds me of a bowl, or the pastern (that part of the horse’s anatomy above the hoof where, the leg is especially thin and tenuous). The tension of the natural world is inspiring to me – sensual and delicious. And I always hope to find ways to use it in the pots I make. My life is also deeply connected to food culture, which is a direct source of inspiration for me. Dining and food presentation, the body of a fish, red peppers in a salad, color, texture – all aspects of the way we appreciate the look of food before we sink into the taste – inform many of the pots I choose to make.

Ultimately, I have a lot of ideas, but to give meaning to my work I have to think and read a great deal. I have to pay close attention to all aspects of the work that comes out of the kiln, to learn where it might lead me next. The pursuit of my vision is still nothing less than a fabulous adventure.

This pursuit is one that, while not losing luster, has maybe grown a little slower. After 40 years in the studio, I realize how the body gives out. Things – tools, bodies – just wear out when you live a physical life. In fact, if I had one practical piece of advice for a young potter, I would advise getting a pug mill early in one’s career. At this stage of my career the studio looks a little geriatric. I do a great deal of carving on leather hard clay and trimming with a sureform tool. In order to keep my head erect, I use a hydraulic banding wheel table on casters, allowing me to easily move the table up and down while working on a form. My chair, also on casters, lifts up and down with the touch of a fingertip. My two potter’s wheels are set at different heights, one for throwing and one for trimming. Also, whenever I am stiff, I hang from a pull-up bar wedged into a doorframe, which loosens my shoulders and spine numerous times a day.

To me, the combination of the need for physical strength, emotional investment, and intellectual acuity to achieve success in pottery is always a challenge, but it is one of unlimited reward. I want to be able to make pots for as long as I can, and will do whatever it takes to keep my studio life viable. I have never been bored by pottery, I still hunger for new exploration, and I look forward to watching new ideas spring forth into real, tangible shapes. Before 1966, I never imagined a person could make a living working all day in a studio surrounded by clay. Today, I cannot imagine my life in any other way.

In the late 1970s, I was hired to be a potter-in- residence at Berea College in Kentucky. Part of the agreement was that I would teach one class each semester and help run the ceramics department’s apprenticeship program, which was part of the college’s “Craft Industries.” The sale of student-made crafts funded a work-study program to pay for the students’ education. By the 1970s, the apprenticeship program at Berea College had existed for many years. I worked there approximately four years and came to value the concept of apprenticeship.

After leaving Berea, my husband and I established working studios in Floyd County, Virginia, a rural community in the Blue Ridge Mountains. It is a progressive and an old-time place at the same time, with beautiful scenery and a community that is very supportive of the arts and music. It’s a good place to be self-employed, but it takes some time to find one’s niche. I have been here for the past twenty-six years.

Dandee Pattee (l) and Silvie Granatelli at the Woodpile. Photograph by Brad Warstler.

After my marriage ended in the mid-1990s, I found myself with what I considered to be a huge studio. The idea of taking on an apprentice came back to me as an option. However, after so many years of working independently in the studio, of making pots that were not production oriented, I wasn’t sure how to develop an apprenticeship relationship with young potters. My problem was really not that I needed help making my “line” of pots, but that I had more space than one potter needs to work in. It took several years and a few false starts before I realized what I could offer besides space.

As well as doing something interesting, I wanted to give something back. I remembered what could have been helpful to me as a young potter, and tried to find ways to provide that help for theirs. When I was beginning, it was hard to invest heavily in equipment, studio space, and materials, to learn how to market what I made, and to present in the best possible way what I wanted to make. Most of all, never having worked in a studio alone, I had no idea how much work it would take to make a living.

Those of us in it for the long haul make our way through these unknowns with varying degrees of success. So I had my expertise to offer, along with space and equipment. I decided to call my appointment an assistantship. Embedded in that concept was also the notion of mentorship. My situation did not fit into the traditional apprenticeship model. It would not be a paid position, and the potters who came to work with me would not make my pots. The exchange would be twelve hours of work each week in return for studio space, the use of studio equipment, and my expertise. I decided to set a specific time commitment of two years, which would give an incoming potter adequate time to develop a body of work, begin to market that work, and make a life in the community.

In the past ten years, I have had five assistants – men and women – each working for about two years. All of them came with undergraduate degrees. I require that they have a good working knowledge of the studio, including the ability to fire a gas kiln and make glazes, as well as some understanding of ceramic materials and processes. Moreover, at this stage they must be interested in becoming professional potters. Whether they end up teaching, being potters, or something else is not important; I only require a commitment to the investigation of being a potter when they begin. It is my hope that they will develop cyclical rhythms of work, learn what it takes to make the amount of pottery that will sustain them in earning a living, and begin to develop ways to present this work to the public. I often say that they have to make the studio the center of their life during this time. Other work, social life, and whatever else they are interested in should fit around this core.

It is important to me to have a professional relationship with my studio assistants. They do not live with me; I only take care of their studio concerns. Many of my assistants have expressed feeling lonely during their first year. Until they develop a relationship to the studio that has deep meaning, this presents a problem. By the second year, everyone has experienced a shift in this regard, enjoying the focus and the time alone to work and think. I believe this is the most frustrating aspect of my relationship with my assistants – to find ways to help them get to this place of rhythm and focus while being alone. I think I do it mostly by example. In each case, I have come to value the friendship that develops. It has been a welcomed bonus, not a prerequisite.

Earthenware platter by Dandee Pattee, 16″ dia.

In the beginning, the studio assistant works at his or her own pace. I encourage them to ask for whatever they need from me; I give critiques, advice, and discourse on request, but I do not direct what they make or how they make it. If after six months they are not developing what I consider to be a committed life in the studio, we have a little chat and agree on an adjustment period to get on track. It is not my intention to make their life easy.

In my opinion, being a potter can be a very humbling experience, especially during the early years when rejection can happen often and money is scarce. I believe it is in our best interest to develop a thick skin. In the end, most potters work alone, from our heads and hearts. We have to develop our own pots – pots that, even though influenced by our teachers and mentors, do not look like someone else’s work. I encourage my assistants to have their own glazes, forms, and ideas, and I try to help them develop this work.

Earthenware pitcher by Dandee Pattee, 8″.

At the beginning of our relationship, the assistants are often reluctant to sell their work. They feel they are not ready, thinking they are not making the kinds of pots they will make later on in their development. I believe it is important to always put our best current work out there and let the people we are trying to communicate with make their own decisions. This will tell us a lot about what we make. At whatever stage of development, there is an audience at about that same level of sophistication. As we grow into our work, our patrons grow with us and we grow, in part, because of them.

The essence of a pot is to give and receive simultaneously, and a potter gives and receives in much the same way. I have worked with Jerilyn Virden, Ian Anderson, Anna Metcalfe, Brian Jones, and Elisa Di Feo; Dandee Pattee is my current studio assistant. My past assistants have all gone on to graduate programs and received degrees. I have felt proud and privileged to work with each of them. They have made my world larger by their unique selves and I hope I have done the same for them.

Using Multiple Layers of Underglaze With Glazes

From Handbuilt Tableware, by Kathy Triplett. Lark Books, 2000. pages. 106-107

Change comes easily to Granatelli (in fact, she says the temptation is to change to much). Her shapes evolve continuously to reflect contemporary cooking trends and eating habits. Her concentration on a particular surface treatment runs in five to eight year cycles. Sometimes she returns to old textures and patterns using different techniques. The fruit forms shown here resulted as a way of establishing a contrast between the voluptuousness of the fruit versus the containment of the pottery form. She enjoys making pots for specific functions, and when she sets her own table for a feast, she combines tableware by many potters as well as industrial ceramics, mixing it all up.

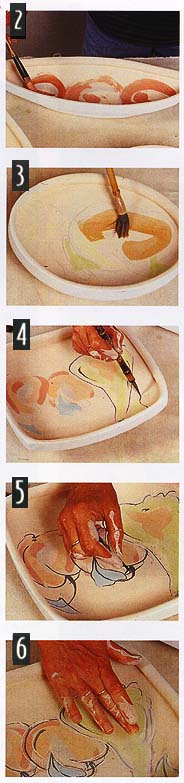

Granatelli begins her glazing technique on several greenware platters that have been hump-molded over plaster forms. She prefers to work on several pieces at one sitting, for efficiency. The platters have extruded feet and rims and pulled handles. She has sprayed a thin layer of underglaze on each.

- She starts by lightly sketching pencil designs on the stain (photo 1).

- Next, she fills in the sketched shapes by brushing on underglazes of yellow, chartreuse, orange, red, tan-taupe, and different shades of green (photos 2 and 3). She handles the brushes with a light, gestural touch, overlapping colors and applying them loosely, so that the brush strokes are visible.

- Using a black underglaze and a small, pointed brush, she outlines the shapes (photo 4).

- With a cutting nail, which is a thick, wedge-shaped nail, she scratches through the designs (photo 5).

- The action creates a powdery residue of underglazes and clay body, which she leaves on the surface.

- (How to #5) After waiting an hour (or overnight), she uses a finger to smudge and blend the residue, which softens the design (photo 6), then she blows off any excess residue.

She bisque fires the pieces to cone 04. After firing, she pours a clear glaze on the insides of the pieces to coat the interiors, then pours it out and wipes off the rims, to remove the glaze from those areas. Using a commercial liquid latex resist, she paints over the clear glaze; she also paints the feet of each piece with a liquid wax resist. She then submerges the pieces in a mate glaze to coat the outsides. The mate will form a nice contrast with the clear glaze on the insides. Finally, she peels off the protective latex and fires the pieces in reduction to cone 9 or cone 10. Silvie Granatelli makes functional tableware and seeks to create a special mood or atmosphere, highlighting food with her beautiful serving pieces. Her Sicilian and Cajun roots contribute to her strong affinity for cooking, hospitality and the ritual of eating. While at the Kansas City Art Institute, she fell in love with Japanese ceramics and English folk pots. Her style has also been influenced by her love of the sensuality of porcelain — the way light gathers in the clay, the way the colors stay bright, and the way it can look liquid, even after it is fired.

Click on the image below to read the article from Ceramics Monthly